Through partnerships with Engel, DuPont and two universities, Winzeler Gear has become one of the world’s top manufacturers of plastic gears, primarily for European automakers. The company’s strategy: Develop a deep understanding of the design, materials and manufacturing of plastic gears by investing in quality equipment and engineering talent; push the envelope by using the latest technology; and reach out to anyone who can improve the process.

“Gear design is a really deep subject,” he said. “We want to be collaborative partners from design forward so we have gear engineers and materials research capabilities so we can execute a complete black-box design.”

Winzeler Gear manufactures 130 million to 140 million plastic gears a year at its plant in Harwood Heights, Ill. The custom gears range in size from about 6 inches in diameter for an automotive transfer application to 0.2 inch. The majority are used with actuator motors in automotive interiors.

“We try to work in components that are safety- critical or mission-critical,” Winzeler said. “We are making fairly inexpensive gears that go into the seats, doors, sunroofs and lots of places.”

Annual sales are about $15 million.

Winzeler Gear’s first strategic partnership started in the 1950s with DuPont, which had a large regional office and R&D center nearby. Harold Winzeler, John’s father and the founder of Winzeler Gear, wanted to better understand plastics and apply it to the gear business, which was transitioning from metal stamping to injection molding.

“At the time, DuPont made nylon and Delrin [acetal homopolymer], which are a couple of our key materials,” Winzeler said. “We were able to acquire knowledge for plastic molding.” Winzeler is still a certified DuPont consumer and works closely with the company.

The relationship has led to improvements in processing crystalline material and use of a DuPont patented screw that is optimized for that type of resin.

“We have access to software that allows us to design our process based on all the tribal knowledge DuPont has provided us,” Winzeler said. The molding process determines the long-term structural integrity and dimensional stability of the part, he said.

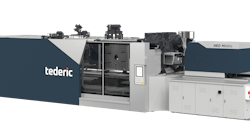

In the very early days, Winzeler Gear used Kawaguchi molding machines. “They were very reliable and affordable presses,” Winzeler said. “They were not very sophisticated, but they got us into the plastics business. As we became more sophisticated, we started shopping around for a press that gave us more control over the process. We looked at Arburg, Battenfeld, Engel — all the obvious players.”

That led to the second strategic partnership, this one with Engel.

Winzeler Gear has used Engel presses exclusively for the past 30 years. The manufacturer currently has 40 presses with clamping forces ranging from 30 tons to 200 tons. Most are Engel e-victory models. The relationship with Engel began when Karl Pieper, then head of Engel North America, promised Winzeler he would never let him down for service and support.

“That’s still true today,” Winzeler said. The relationship has grown to the point that Engel’s regional sales representative has his office in the Winzeler Gear plant and carries a key to the front door.

“I have the personal email of the president of Engel in Austria. Do we ever have problems? Absolutely, but we are in the partnership to succeed together,” he said. Engel is globally competitive and continually reinvents itself, two important characteristics for Winzeler.

Winzeler Gear does not buy many presses from Engel but by developing strong ties with the manufacturer — starting when it purchased its first Engel press — it takes advantage of the latest technology and expertise from the machinery maker.

For instance, it is currently implementing Engel’s vision of Industry 4.0, which it believes will eventually lead to improved manufacturing efficiency.

It is handicapped by the low ceilings prevalent in manufacturing spaces from that era. “We don’t have the height for cranes and that has driven some decisions on how we move stuff,” Winzeler said. “Engel helped us go to a quick mold-change system, and we spent a lot of money on how we store and move molds.”

Winzeler built mold storage racks that are compatible with a modified gantry truck that can then be wheeled to the press. One person can handle the entire process and no overhead cranes are needed.

Most of the molds used by Winzeler Gear are high-precision, with four or eight cavities. Many of the gears have tolerances in the micron range.

Typical production runs range from two to three days to two to three weeks. There are two or three mold changes a day, on average. “We try to avoid low-volume products,” Winzeler said.

Each work cell is created to run without an operator. “We don’t have any operators,” Winzeler said. “If you want to make a consistent product, the last thing you want is a human involved.”

Although people working at machines are scarce, Winzeler Gear is not a lights-out operation. Every two to three hours, sample parts are brought to the process inspection lab to be examined. Parts can be traced to a specific lot.

Winzeler said he has attempted to implement in-line testing but has not yet managed to accomplish it satisfactorily. He said he thinks that eventually a shortage of workers will mean two shifts will have to run lights-out. “We will have to figure out the QC issues,” he said.

Winzeler considers RJG a partner, and the company is a beta test site for new RJG products.

Winzeler is a believer in RJG’s eDart process control and monitoring system.

“We must get an OK signal from eDart to allow parts to be picked by the robot,” Winzeler said. “The first gate is the signal from eDart. If we cannot get that signal, we cannot run the machine.”

Every mold cavity is equipped with a pressure sensor. The plant’s 180 WiFi devices transmit data from the sensors wirelessly to a blade server.

“We are making sure we are rock-solid because if that network doesn’t run, our plant doesn’t run,” he said. “We have had that in place even before starting on Industry 4.0.”

There are three RJG-certified Master Molders at Winzeler Gear, including the VP of operations.

“I try to have one philosophy for molding, and that is RJG’s Master Molder Decoupled thinking,” Winzeler said. RJG’s approach involves determining the optimal velocities and pressures for each of the three stages of the molding process: fill, pack and hold.

“We are collecting data from the eDarts. We don’t do much with it yet.”

To leverage the eDarts, the company has a partnership with Northwestern University’s school of industrial design. As part of the partnership, five students are working on how to use the data. “We hope they will help us move forward faster,” Winzeler said.

The company once tried to replace molding machines when they were 10 years old. “We failed in that goal,” Winzeler said. Customers are reluctant to allow Winzeler Gear to switch machines or update molds after a process has been certified.

Also, there is no space to put a new machine next to a current machine, requalify the new machine and transfer the work while maintaining production. “It has become a nightmare,” Winzeler said. “Thank goodness Engel makes a durable machine.

“We have some programs going obsolete soon that will provide some pockets for growth,” he said. “That will be our next project. I never thought our customers would dictate when we could change machines, but they do.

“I understand their concern because they probably have been hurt by molders who don’t know what they are doing,” Winzeler said. “If people understood how we go about it, it should not be such a big deal.”

Winzeler said he has one customer he has been trying unsuccessfully to convince to switch to a high-cavitation tool for more than three years. “So, we are still running an old, tired tool,” he said.

Winzeler said Industry 4.0 should help with the company’s total predictive maintenance program.

A variety of OEMs have supplied Winzeler’s equipment.

Labotek A/S supplied the plant’s central system for materials handling. Winzeler Gear first bought Labotek equipment when machine-mounted dryers were on each press. When the company decided to switch to a central system, Labotek was on the short list because Winzeler was comfortable with the Danish company’s quality. “They were one of the only companies that didn’t go to the hardware store to buy parts. For many years, we could not find workmanship like that in this country,” he said.

Regloplas Corp. supplied temperature-control units.

Engel provided beam robots, while Fanuc supplied most of the plant’s other robots.

In addition to its lab for testing finished products, Winzeler Gear has a lab where the company’s senior gear metrologist researches new products. “What makes us different from just a molding plant is that this lab has about $2 million in gear metrology testing equipment,” Winzeler said. The development and testing performed in this lab at the front end of new projects is critical to Winzeler Gear’s business, he said.

Bradley University maintains a lab in the company and provides a professor for gear testing. Winzeler graduated from Bradley with an engineering degree.

Even though product development is important to the company’s business plan, Winzeler has not incorporated 3-D printing. He said the materials used in gears cannot currently be 3-D printed. Instead, to test gears, Winzeler Gear builds a single-cavity steel tool with the same valves and gating that would be used in the multi-cavity production tool.

“Our customers want a prototype they can test for quality, sound and performance, with no exceptions,” he said. Gears must not only work well; they have to be quiet enough to meet customers’ requirements.

There is a major technical gear research and design conference every other year at the University of Munich that brings together experts from all over the world. Winzeler and his gear engineer went to the last conference, and it is influencing the company.

“We sat in a big auditorium and heard the German engineering association tell us how they were going to dominate machinery and manufacturing by embracing Industry 4.0,” Winzeler said.

Engel partnered with, then purchased TIG as part of its Industry 4.0 program. TIG creates the manufacturing execution system that collects and displays data in a factory. Winzeler Gear currently has five presses connected to the TIG system.

“We are trying to use the incentive of Industry 4.0 to force us to really understand what we are and are not from an overall equipment efficiency standpoint,” he said.

“We are out of bricks and mortar, so how do we get more work out of this building? The customer does not want to pay for waste,” he said.

For an American company driven to meet European standards, sitting in a conference isn’t enough — Winzeler is now gearing up to present a technical paper at the Munich conference later this year. Personnel from its partners, DuPont and Bradley University, also are part of the group.

Taking molding to the next level will require more than just machines; Winzeler knows the future is in implementing Industry 4.0.

SIDEBAR: SUPRISES BEYOND ITS DOORS

There are mannequins wearing gear jewelry and dresses. Artistically photographed gears are on the walls throughout the plant. There is sculpture, as well.

“We are trying to change the way people think about manufacturing,” said owner John Winzeler.

Some of the pieces were created by professional designers and others by art students, with scholarship money provided to the winners. The company commissions artists from all disciplines to reimagine gears.

It is all about the collaboration of creative people and technical people, he said. The art creates an atmosphere that encourages creative thought that can carry over into gear design.

It also is fun and presents an unusual image for a manufacturing plant.

Ron Shinn, editor

Contact:

Winzeler Gear Harwood Heights, Ill., 708-867-7971,